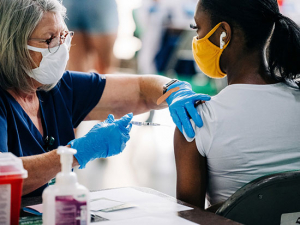

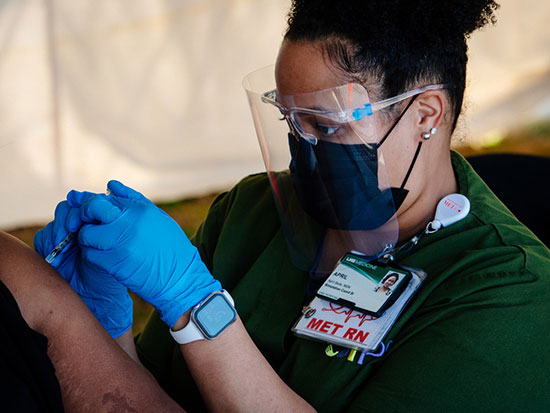

In his nearly 30 years studying vaccines, UAB’s Paul Goepfert, M.D., director of the Alabama Vaccine Research Clinic, has never seen anything as effective as the three COVID-19 vaccines — from Pfizer, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson — available in the United States. “A 90% decrease in risk of infections and 94% effectiveness against hospitalization for the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines is fantastic,” he said.

In his nearly 30 years studying vaccines, UAB’s Paul Goepfert, M.D., director of the Alabama Vaccine Research Clinic, has never seen anything as effective as the three COVID-19 vaccines — from Pfizer, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson — available in the United States. “A 90% decrease in risk of infections and 94% effectiveness against hospitalization for the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines is fantastic,” he said.

But what makes vaccine experts such as Goepfert confident that COVID vaccines are safe in the long-term? We all have seen billboards and TV infomercials from law firms seeking people harmed by diet drugs or acid-reflux medicines for class-action lawsuits. What makes Goepfert think that scientists won’t discover previously unsuspected problems caused by COVID vaccines in the years ahead?

There are several reasons.

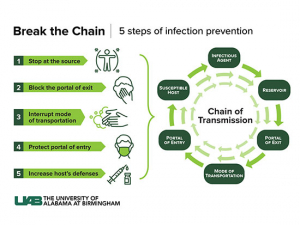

- Vaccines are eliminated quickly

- Vaccine side effects show up within weeks if at all

- Our COVID vaccine experience during the past six months

Vaccines, given in one- or two-shot doses, are very different from medicines that people take every day, potentially for years, Goepfert says. And decades of vaccine history — plus data from more than a billion people who have received COVID vaccines since December 2020 — both provide powerful proof that there is little chance that any new dangers will emerge from COVID vaccines.

The majority of Americans who haven't been vaccinated — or who say they are hesitant about vaccinating their children — report that safety is their main concern. Nearly a quarter (23%) of respondents in Gallup surveys in March and April 2021 said they wanted to confirm the vaccine was safe before getting the shot. And 26% of respondents in a survey of parents with children ages 12-15 by the Kaiser Family Foundation in April 2021 said they wanted to “wait a while to see how the vaccine is working” before deciding to get their child vaccinated.

But do we already know enough to be confident the COVID vaccines are safe? Yes, Goepfert said. Here's why, starting with the way vaccines work, continuing through strong evidence from vaccine history and the even stronger evidence from the responses of people who have received COVID-19 vaccines worldwide during the past six months.

1. Vaccines are eliminated quickly

Unlike many medications, which are taken daily, vaccines are generally one-and-done. "Medicines you take every day can cause side effects" that reveal themselves over time, including long-term problems as levels of the drug build up in the body over months and years, Goepfert said. But "vaccines are just designed to deliver a payload and then are quickly eliminated by the body," he said. "This is particularly true of the mRNA vaccines. mRNA degrades incredibly rapidly. You wouldn't expect any of these vaccines to have any long-term side effects. And in fact, this has never occurred with any vaccine."

2. Vaccine side effects show up within weeks if at all

That is not to say that there have never been safety issues with vaccines. But in each instance, these have appeared soon after widespread use of the vaccine began. "The side effects that we see occur early on and that's it," Goepfert said. In virtually all cases, vaccine side effects are seen within the first two months after rollout.

The only vaccine program that might compare with the scale and speed of the COVID rollout is the original oral polio vaccine in the 1950s, Goepfert says. When this vaccine was first introduced in the United States in 1955, it used a weakened form of the polio virus that in very rare cases — about 1 in 2.4 million recipients — became activated and caused paralysis. (Compare this with the 60,000 children infected with polio in the United States in 1952, and the more than 3,000 children who died from the disease in the U.S. that year.) Cases of vaccine-induced paralysis occurred between one and four weeks after vaccination. None of the COVID vaccines uses a weakened form of the SARS-CoV-2 virus — all train the body to recognize a piece of the virus known as the spike protein and generate antibodies that can attack the virus in case of a real infection.

In 1976, a vaccine against swine flu that was widely distributed in the United States was identified in rare cases (approximately one in 100,000) as a cause of Guillain-Barré Syndrome, in which the immune system attacks the nerves. Almost all of these cases occurred in the eight weeks after a person received the vaccine. But the flu itself also can cause Guillain-Barré Syndrome; in fact, the syndrome occurs 17 times more frequently after natural flu infection than after vaccination.

In 1999, a vaccine against rotavirus, which can cause life-threatening diarrhea in infants, was pulled from the market after more than a dozen cases of bowel obstruction were reported in the first six months of use. (After an extensive review of records, the case rate was determined to be about one case per 10,000 doses.) The greatest risk was found to be within three to seven days after the first dose of the vaccine. "When they gave it to millions of kids, they discovered this very rare effect of intussusception, or bowel obstruction, which occurs with rotavirus as well," Goepfert said. “And the vaccine was quickly removed from use.”

3. Our COVID vaccine experience during the past six months

By the time the Pfizer and Moderna COVID vaccines were approved for emergency use in the United States in December 2020, "we already knew the short-term side effects very well from the efficacy studies," Goepfert said. Pfizer and Moderna — and later Johnson & Johnson and then Novavax, which reported on its Phase III trial results in June 2021 — "all have enrolled 30,000-plus individuals, half of whom got the vaccine and half of whom got a placebo initially, after which all the placebo group got the vaccine," Goepfert said.

The side effects seen in these studies, and again in the nationwide rollouts that began in December 2020, "were tolerability issues," Goepfert said: "mainly things like arm pain and fatigue and headache. They are very transient and occur a day or two days after the vaccine" and then resolve quickly.

As of June 12, 2021, more than 2.33 billion COVID vaccine doses have been administered worldwide, according to the New York Times vaccinations tracker.

Between December and June, "we have seen the more-rare things that you don't find until you start giving the vaccines to millions of people, the side effects that occur in about one in 100,000 or one in a million people," Goepfert said.

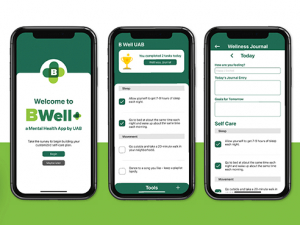

Find a vaccine todayUAB students, employees patients and community members can make a vaccine appointment or find walk-up sites at uab.edu/uabunited/covid-19-vaccine. |

About one in 100,000 people receiving the AstraZeneca COVID vaccine have experienced a clotting disorder known as thrombotic thrombocytopenia, including 79 cases among more than 20 million people receiving this vaccine in the United Kingdom, and 19 deaths. A smaller number of cases have occurred with Johnson & Johnson's vaccine as well, Goepfert said. "The causes are still being worked out, but when this happens it occurs from six days to two weeks after vaccination," he said. (See the CDC summary and FAQs on Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine here. See a study on these cases in the AstraZeneca vaccine in the New England Journal of Medicine here and a report from the British government’s regulatory agency here.)

More recently, an even more rare side effect — myocarditis, or inflammation of the heart muscle — has been reported in people receiving Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines. "That is about one in a million, or possibly higher rates in some populations, but again all of these occur no more than a month after the vaccination," Goepfert said. (The majority of 285 cases reviewed by the CDC were mild.)

On July 12, 2021, the FDA announced that in rare cases (100 reports out of 12.8 million shots given in the United States), the J&J vaccine is associated with Guillan-Barré syndrome. The cases were mostly reported two weeks after injection and mostly in men age 50 and older.

"Many people worry that these vaccines were rushed into use and still do not have full FDA approval — they are currently being distributed under Emergency Use Authorizations," Goepfert said. "But because we have had so many people vaccinated, we actually have far more safety data than we have had for any other vaccine, and these COVID vaccines have an incredible safety track record. There should be confidence in that."

Weighing the odds

Any risk is frightening, especially for a parent. But the rare side effects identified with COVID vaccines have to be weighed against the known, higher risks from contracting COVID, Goepfert says. It is not clear how COVID variants such as the highly infectious Delta mutation first seen in India may affect patients. Early indications are that Delta infections bring more severe side effects than other forms of COVID, but that vaccines are still protective against Delta.

It is COVID infection, and the growing evidence of persistent symptoms from what has become known as “long COVID,” that are the most troubling unknown out there, says Goepfert. Even as cases, hospitalizations and deaths have declined significantly in Alabama since January, there are still nearly 250 new COVID cases diagnosed and nearly 10 deaths reported statewide per day as of mid-June.

“The long-term side effects of COVID infection are a major concern,” Goepfert said. “Up to 10 percent of people who have COVID experience side effects” such as difficulty thinking, pain, tiredness, loss of taste and depression. “We don’t know why that is, how long these symptoms will last or if there are effective ways to treat them. That is the most troubling unknown for me.”